Madie Spartz, Norzin Waleag, Elizabeth Fontaine, and Merle Greene

College Readiness Academy (CRA) is an innovative program model providing both academic instruction and wrap-around advising services to college-bound Adult Basic Education (ABE) students. This article explains CRA’s rationale and methods for implementation, including a sample lesson plan, outcomes, and potential for replication.

Key words: College readiness, developmental education, equity, remediation, navigation

College Readiness Academy (CRA), offered by the International Institute of Minnesota (the Institute), is an innovative model with proven success in preparing college-bound adults for college-level coursework. CRA helps bridge the achievement gap that many first-generation, college-bound new students experience in higher education. By fully integrating intensive academic skill-building with proactive navigation services, CRA helps students overcome academic and personal obstacles to college success. The overall goal of CRA is to provide a seamless transition to college by offering an alternative to the post-secondary, remedial (sometimes called developmental) education system, which can increase college retention and graduation rates, while also saving time and money. In this article, the authors—CRA instructors and navigators—highlight the challenges that led to the development of CRA, describe the classes and navigation system, and demonstrate how the CRA model might work for students

The Problem

The CRA Partnership was launched in 2015 in response to the frustrations expressed to us faced by graduates of the Institute’s nursing assistant training program as they attempted to enter college nursing programs. The stories of struggle had a common theme: students had been assigned to mandatory developmental education (ESL, reading, and writing classes offered at colleges), and they were spending many semesters in these courses. This, in turn, created a barrier to enrolling directly in the college-level prerequisite courses needed for nursing programs. This anecdotal evidence has been echoed in national studies as well. The U.S. Department of Education found that 68% of all public two-year students are placed into remedial coursework (Chen, 2016, p. 16). Moreover, students entering remedial education very often do not make it beyond that point. The students placing into these classes are “74% more likely to drop out of college than first-time, full-time, non-developmental students” (Schak, Metzger, Bass, McCann, & English, 2017, p.7). Barry and Dannenberg (2016) indicated that students who take even one remedial class at post-secondary institutions are far less likely to graduate with an associate or bachelor’s degree than students who begin taking college-level classes.

This is not only an issue of graduation rates. Developmental education classes are tuition-based, so students unfamiliar with the post-secondary system in the US might assume them to be college-level, credit-bearing coursework. In some cases, students have used critical financial aid resources for these classes. Prospective CRA students at the Institute often ask us about the remedial coursework: “Will this class listed on my transcript give me credit like college classes do?” The message is clear: many of our students have mistakenly believed that remedial classes award credits that count toward their degrees. Because they typically do not, such developmental classes can be a costly alternative to the free preparation available through Adult Basic Education (ABE) in Minnesota.

Who is Impacted

The populations most affected by placement in remedial education programs are students of color, first-generation college students, English language learners, and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (Academic and Student Affairs, 2018a). Among all beginning postsecondary students, an estimated 58 percent of Hispanic students, 57 percent of black students, 39 percent of Pell Grant recipients, and 40 percent of first-generation college students enrolled in a developmental course between 2010 and 2014 (King, McIntosh, & Bell-Ellwanger, 2017).

Moving in a New Direction

Recognizing the challenges that face students who place into remedial courses, Minnesota State created a Developmental Education Strategic Roadmap, which outlines Minnesota State’s collective initiative for revamping the Developmental Education system (Academic and Student Affairs, 2018b). They hope to “re-imagine how students are placed into developmental or college-level courses, as well as how students can successfully complete required developmental-level courses and subsequent college-level gateway courses, enabling them to be on-track in the first year of pursuing their academic program” (p. 3). In fact, Strategic Goal 3.3 charges Minnesota State colleges to “Establish and/or strengthen partnerships with Adult Basic Education, community organizations, and/or other student support services (e.g. TRIO) to provide support for students in developmental education”(p. 2). Goal 5.3 requests they “Establish and/or strengthen bridging options that facilitate student placement into college-level courses (i.e., partnership with Adult Basic Education, summer bridge program, boot camp, course placement assessment prep, etc.)” (p. 2). Moving in this direction will improve partnerships with ABE and make college more affordable to students placing into remedial levels. One solution already in place within ABE is College Readiness Academy (CRA), which provides free college preparation in addition to ongoing navigation throughout the students’ college experience until graduation.

College Readiness Academy

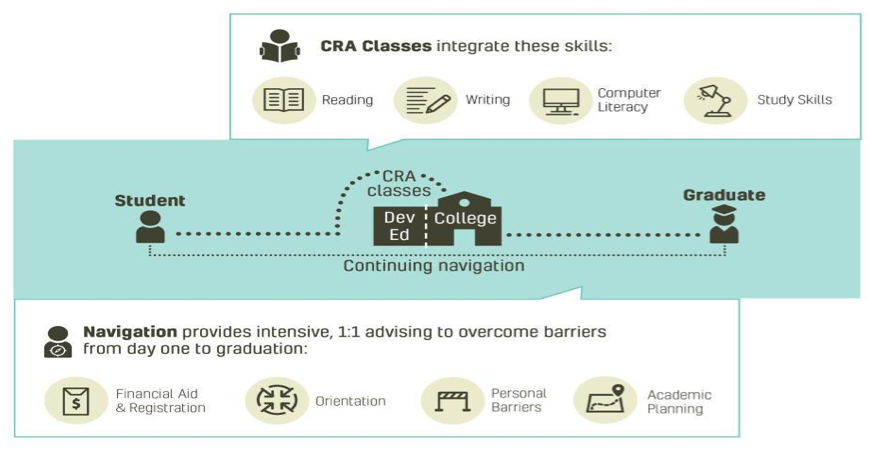

CRA is an effective and free approach that integrates academic skill-building focused on reading, writing, digital literacy, and study skills with intensive navigation (see Figure 1). The navigation typically includes guidance on issues like paying for school, campus culture, and overcoming barriers to progress.

Currently, CRA classes take place at three sites: The International Institute of Minnesota, Hubbs Center for Lifelong Learning, and Saint Paul College. Over the past three years, CRA graduates have moved on to college bypassing an average of 1.5 semesters of developmental education. Of the college-bound students who have completed CRA since 2015, our program has tracked that over 150 have enrolled in college-level courses and programs. Moreover, 90% of these students have persisted beyond the first semester in college, and their average GPA is above 3.5. Additionally, CRA navigators have helped students apply for and earn over $290,000 in college scholarships. CRA students are graduating with a certificate or associate or bachelor’s degree, majoring in a range of programs from nursing to accounting to computer science. By helping to bridge the opportunity gap through academic preparation and navigation support, CRA has increased access to higher education and ultimately to jobs and careers with family-sustaining wages.

In addition to the internal data tracked on students, we have also conducted external evaluations. The most recent evaluation in 2019 conducted by external consultants, The Improve Group, found that “CRA students earn more credits, are more likely to stay enrolled at college, and are more likely to graduate than Developmental Education students. CRA students may be more likely to succeed because of the academic skills and familiarity with the college campus they develop during the program. CRA students are also more likely to stay the course, in part because of the intensive support they receive from CRA navigators” (p. 3). Another interesting statistic is the comparison in credits earned by students who were able to earn a C or higher. And lastly, the evaluation also showed that “On average, CRA students enroll in more credits over their academic careers than [Developmental Education] students, resulting in higher per-student revenue for the colleges” (p. 5).

The evidence reported by the Improve Group (2019) and our own experience with learners indicates that CRA is a viable solution to the disparities in educational attainment and income by primarily serving low-income students of color, including New Americans.

The CRA Classroom

There are a number of defining characteristics of CRA that contribute to the success of our students academically, including skills integration in class, more class time, a cohort model, and integrated learning objectives.

Skills Integration

CRA lessons are organic in terms of skill-building because all of the academic components—literacy, oral, computer, and study skills—are fully integrated. Speaking activities, for example, reinforce new vocabulary and give students time to process reading content in preparation for writing tasks. There is a long list of measurable integrated skills objectives that students are assessed to achieve:

- Identify the differences between fiction and nonfiction materials.

- Identify the stated or implied main idea of an academic reading.

- Focus, read, and apply critical reading skills to college-level texts.

- Prewrite and write varied and clear sentences.

- Practice process-writing.

- Write summary and synthesis paragraphs.

- Practice writing an essay.

- Formally summarize a variety of college-level materials, such as articles, editorials, and lectures.

- Use various strategies for developing vocabulary.

- Paraphrase main ideas and major supporting details of a variety of text types, with an emphasis on textbook reading.

- Synthesize information from multiple sources on a topic.

- Utilize graphic organizers to structure paragraphs, essays, and presentations.

- Enhance Accuplacer skills.

- Increase computer competency in typing, Microsoft Word and PowerPoint, and Google Docs.

- Complete homework.

- Keep a weekly schedule.

See Appendix A for a step-by-step lesson plan from a CRA classroom to see how these components are integrated into lessons.

Intensive Instruction

In CRA, students have abundant face-to-face time with instructors: about twelve hours/week. CRA’s concentrated in-class time is a significant benefit to a student population that needs extra guidance with the opportunity to work in a quiet, focused atmosphere. When students undertake out-of-class assignments, extra class time allows the instructor to monitor their first steps, confirm they are on the right track, or redirect when they are not, before they commit time to a misguided task.

Cohort model

Another important feature of CRA is its strong student cohort. The Power of a Cohort and Collaborative Groups published by the National Center on the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy explored the use of cohorts in ABE and ESL settings, recommending that educators develop an “enduring and consistent learner cohort, employing practices by which students are regularly invited to engage in collaborative learning” (Drago-Severson, Helsing, Kegan, Popp, Broderick, & Portnow, 2001, p. 22).

CRA implements the cohort model; through managed enrollment and an intensive 12-hour-a-week schedule, students work with the same group of learners every day. Moreover, a significant proportion of class time is spent in pair work or small group activities. During this time, students negotiate meaning and share insights with peers, fostering group cohesion. Also, the classroom is configured such that 4-6 students sit around each table, which also encourages collaboration. And another way that CRA exemplifies the cohort model is by making sure the reading and writing tasks are based on socially relevant topics, encouraging students to have conversations that go deeper and build both self-knowledge and stronger relationships with peers. Individual and group presentations on these topics help students from diverse cultures to recognize their similarities.

All of this fosters a greater motivation and learning: “… cohort experiences seem to facilitate academic learning, increased feelings of belonging, broadened perspectives, and, at least by our participants’ report, learner persistence” (Drago-Severson, et al., 2001, p. 22). We continue to see evidence of the effectiveness of a strong learner cohort when students discuss assignments the moment they walk into class, when they stay after class to help one another, when they share personal stories, and when their relationships continue into college.

College Navigation

The inability to navigate college systems is a major obstacle to student success. In response, CRA incorporates proactive college navigation to help students prepare for college and complete their degrees. College navigators work with students step-by-step from their initial CRA class until they graduate from college. Unlike college advisors, who usually have hundreds—if not thousands—of students, college navigators usually work with approximately 50 students at a time (Robinson, 2016). This allows navigators to offer students the intensive case management they need as well as the wrap-around services that enable them to stay in school.

The navigators are present in class both as supplemental instructors and as participants on a weekly basis, assisting the instructor, interacting with students, and monitoring their progress. This allows them to build a meaningful relationship with each student by becoming familiar with their goals and life circumstances. Supplementing classroom navigation with effective individual support is only possible when there is a reasonable navigator/student ratio.

“For me the problem with college is not the concepts. It’s how to better understand what I had to do. Without CRA I think it would have taken me a long, long time.”

-Gnande, CRA Graduate

College navigators’ support to students includes:

- Accuplacer testing

- Registration

- Development and delivery of curriculum to each class on a variety of subjects, including financial aid, time management, self-advocacy, and choosing a major

- Assistance with completing FAFSA and related documents

- Assistance with scholarship applications

- Delivery of orientations each semester for students ready to begin college

- Goal-setting, both academic and personal, short-term and long-term

- Assistance with college applications and registration

- Troubleshooting with admissions, enrollment, financial aid, foreign education accreditation, transfer issues, and other barriers to graduation

- Academic support such as feedback on assignments and referrals to on-campus resources

- One-on-one advising to overcome personal barriers to college success, such as loss of employment, child care challenges, and housing struggles through hands-on referrals

“I learned in classes to express myself and to use my critical thinking skills to solve problems. The navigator is always available to answer questions and helps to put in place the college process.”

-Christelle, CRA graduate

Initiating and Sustaining CRA

An obvious first step to establishing a high-quality college readiness program is to build a team of experienced instructors and navigators. CRA instructors have had combined experience in adult basic education, ESL instruction, and higher education. Navigators typically bring experience with college access organizations or social work. Regardless of professional background, it is critical for instructors and navigators to be flexible, dynamic, creative educators and problem-solvers. Working with a diverse adult population at a variety of sites necessitates a willingness to adjust practices to best fit the needs of the particular group. In order to build trust between navigators and students, navigators are fully integrated into the classroom.

In order for a program to be viable and to improve over time, it is imperative to collect comprehensive data, including student educational background information, progress, and outcomes. Funders will want detailed information on demographics, success rates, and many other metrics, so a uniform method is needed for tracking pertinent information. A customer relationship manager (CRM) is a beneficial tool for data tracking and synthesis. A strong program will also perform frequent self-evaluation and adjust methods accordingly; a CRM is useful for this practice as well. Some examples of frequently accessed metrics include:

- Number or proportion of students making a “level gain,” therefore bypassing some or all of developmental education classes at the college

- Amount of money saved by students attending CRA rather than paying tuition for developmental education classes

- Number or proportion of students who advance to college and graduate

Finally, one of the most important elements of creating a successful, sustainable college readiness program is building and maintaining relationships and institutional trust with local colleges, which requires significant time and effort. This process is ongoing and constantly evolving, but the more support a college can give the program, the more impact the program can have. The relationship is symbiotic: CRA provides colleges with a steady stream of prepared, motivated students; in turn, the college can afford CRA students unique benefits, including increased academic support, flexibility with entrance requirements, and exemption from college entrance exams. Perhaps most importantly, students will gain trust in the college and become fully confident in their identity as college students and, ultimately, graduate.

References

Academic and Student Affairs. (2018a). Developmental education plan report to the legislature. Minnesota State. Accessed 1 November 2019 at http://www.minnstate.edu/system/asa/docs/Minnesota%20State%20-%20Developmental%20Education%20Plan%20Report%20to%20the%20Legislature%20-%202.15.18.pdf

Academic and Student Affairs. (2018b). Developmental education strategic roadmap: Minnesota State’s strategic plan for developmental education redesign. Minnesota State. Accessed 1 November 2019 at http://www.minnstate.edu/system/asa/studentaffairs/academicreadiness/docs/Developmental-Education-Strategic-Roadmap.pdf

Barry, N. G., & Dannenberg, M. (2016). Out of pocket: The high cost of inadequate high schools and high school student achievement on college affordability. Education Reform Now. Accessed 1 November 2019 at http://edreformnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/EdReformNow-O-O-P-Embargoed-Final.pdf

Chen, X. (2016). Remedial course-taking at U.S. public 2- and 4-year institutions: Scope, experiences, and outcomes (NCES 2016-405). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Accessed 1 November 2019 at https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016405.pdf

Drago-Severson, E., Helsing, D., Kegan, R., Popp, N., Broderick, M., & Portnow, K. (2001). The power of a cohort and of collaborative groups. NCSALL. Accessed 1 November 2019 at http://www.ncsall.net/index.php@id=254.html

King, J. B., McIntosh, A., & Bell-Ellwanger, J. (2017, January). Developmental education challenges and strategies for reform. U.S. Department of Education. Accessed 1 November 2019 at https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/opepd/education-strategies.pdf

Robinson, W. (2016). Community college academic advisors and the challenge of access in the age of completion (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Iowa State University, Ames, IA. Accessed 1 November 2019 at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6062&context=etd

Schak, O., Metzger, I., Bass, J., McCann, C., & English, J. (2017). Developmental education challenges and strategies for reform. U.S. Department of Education. Accessed 1 November 2019 at https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/opepd/education-strategies.pdf

The Improve Group. (2019). College Readiness Academy (CRA) 2018-19 Evaluation Findings. St. Paul, MN: The Improve Group.

Appendix A

Example of Step-by-Step of Skills Integration in CRA Classroom

Authentic reading: Adapted from “The Perils of Polygamy”, published in The Economist – December 23, 2017

This article claims that polygamy is responsible for instability and violence in South Sudan. The instructor abbreviated it somewhat and added footnotes for essential vocabulary that could not be understood from context. The class approached the article like this:

- Students completed a pre-reading worksheet: they analyzed select sentences for cause-and-effect and compare-contrast relationships, and practiced prediction skills.

- Class generated a list of questions they wanted answered by the text.

- Class read the text aloud.

- Pairs re-read and annotated the text, paragraph by paragraph, looking for answers to their questions.

- Class generated a list of the benefits and drawbacks of polygamy.

- Pairs developed a graphic organizer of the cause-and-effect chain of events that led from the practice of polygamy to social instability.

- Students explained the content of the article to a partner using word prompts that included new vocabulary and then repeated the task with a different partner until ideas became clearer, language more fluent, and new vocabulary more familiar.

- Students wrote one-sentence and one-paragraph summaries of the article.

- Class conversation drew on students’ personal reactions to the text. Two students had actually had family experiences with polygamy. Instructor then posed questions that encouraged deeper analysis, including practice of TABE and Accuplacer-style reading skills. Students broke into small groups for discussion, and then debriefed together.

- What was the author’s purpose? Claim? Tone?

- What important content was omitted from the article?

- What changes would have to occur in South Sudan in order for the incidence of polygamy to decrease?

- A variety of vocabulary activities – written, aural, and oral – punctuated the lesson such that, in the end, students were able to contextualize at least 16 formerly-unfamiliar words from the text that are commonly found in academic readings.