Martha Bigelow

In this article, Dr. Bigelow describes her first-hand experience learning about multilingual resources and educational practices found in a refugee camp in Djibouti. Dr. Bigelow reflects on the importance of educators truly understanding the pre-resettlement experience of their learners and marvels that linguistically and culturally relevant multilingual resources not often found in schools in the U.S. are in use in refugee camps in the Horn of Africa.

Key words: refugee, East Africa, SLIFE, Djibouti

The proverb in my title is a carpe diem sort of Somali proverb that I learned in Djibouti, written here in Somali and in Arabic on a map in my office in Peik Hall at the University of Minnesota. It captures the urgency I feel when I think about education for refugee-background youth all over the world, but especially those here in Minnesota. It inspires me.

In Minnesota, we have an enormous amount of experience with refugee-background students, starting in the 1970s when so many Hmong families were given their well-earned asylum here. In fact, we are looked to across the nation for our expertise with the widely diverse needs of this slice of our English learner population. Note, for instance, the consistently strong showing at our annual and always homespun MinneSLIFE conference (http://minneslife.org/), that is now drawing participants and presenters from around the world. We can see Minnesota leadership on teaching adults who are new to print on the pages of the Literacy Education and Second Language Learning for Adults (LESLLA) symposia proceedings, starting back in 2005 (https://www.leslla.org/). We seem to be continually learning, re-learning, and un-learning about culturally responsive pedagogies that help refugee-background English learners develop print literacy and the myriad other skills they seek in order to reach their goals as they make new lives in the diaspora. There is no end to what educators need to know about teaching their refugee-background students, but it seems that one of our most significant gaps is what we know about our students’ pre- and during-migration experiences. We need to nuance, trouble, de-essentialize, and complicate our notions of our students’ pre-resettlement experiences in order to discover, amplify, and leverage their many gifts and assets for joyful, productive classroom learning experiences.

At the same time, it’s impossible for most of us to comprehend the pre-resettlement experiences of the refugee-background students in our classrooms. We listen to and read personal accounts of the experiences of displacement—so varied, but often terrible and so protracted.1 Narratives often repeat—girls with less access to education, child soldiers, lack of educational materials, enormous class sizes, injuries, violence, and illnesses suffered from displacement and en route to a refugee camp and also after arrival to the camp. That students will have had inadequate, limited or interrupted formal schooling is an overarching assumption among us when we meet a refugee-background student from the Horn of Africa (the Horn), and particularly from Dadaab refugee camp. Camps in Djibouti are different, which I learned during a recent visit. These camps, and the Djiboutian multilingual educational system in general, gave me pause, making me imagine a more multilingual Minnesota and the possible need for different first educational encounters with newcomers from the Horn. Djibouti showed me that we all need to explore, in our own way, the pre-resettlement experiences of our refugee-background students, but travel to the Horn is transformative.

I have learned some important lessons about newcomers through the locally-produced, community-engaged, and highly collaborative research I’ve done with teens from the Horn, their teachers, and my co-authors. We have discovered, for example, that even though the newcomers have physically crossed (many) borders, they have still been shaped by their pre-resettlement experiences. These experiences matter as we seek to understand language learning in post-migration contexts. We have seen how boys often adjust to the ordinary routines of formal schooling in the U.S. fairly easily because of previous schooling and print literacy, even if interrupted, and their prior schooling and literacy often converts into status in classrooms (Bigelow & King, 2014). Reasons for a gender gap can easily be traced to reports such as those produced by the UNHCR, clearly documenting the need to prioritize refugee girls’ education in pre-resettlement contexts. When inequities occur pre- and during-migration, it is clear that these inequities will follow youth into their places of resettlement. The dynamics among refugee-background youth, in the powerful social context of a newcomer classroom, will shape opportunities to engage in learning. As newcomers are adjusting to the routines and new cultural and linguistic practices of their classrooms (King & Bigelow, in press), they are growing new identities as cultural beings, as capable problem-solvers, and as students through family and community relationships as well as at school (Bigelow, in press). The more we know about pre- and during-migration experiences, the more we can legitimize the knowledge and skills of our refugee-background youth to be supportive of these educational processes (Bigelow, 2010; Bigelow & King, 2016; Bigelow, Vanek, King, & Abdi, 2017; King & Bigelow, 2018; King, Bigelow, & Hirsi, 2017).

Going to the Horn for the First Time

In March this year, I traveled to Djibouti with two remarkable and visionary educators—Jill Watson (St. Olaf College) and Ryan Krominga (Faribault Public Schools)—to visit schools and a refugee camp and learn about the Horn, a region that is so important to Minnesota. Jill and I had been dreaming about such a trip for at least ten years and the idea of partnering with a school district to create ways educators could learn about pre-resettlement contexts started to take shape. Jill started working on this project in 2015 and plans to take a small group of students and educators from Minnesota to Djibouti to learn about the Horn and pre-resettlement experiences, and to collaborate with educators there. But before that, she needed to go herself and invited me to join her. Ryan became an enthusiastic partner because of the many students Faribault Public Schools has from the Horn. We hope that more educators from Faribault Public Schools will go in the future.

Why Djibouti? We wanted to visit East Africa, particularly a Somali homeland, considered by many to be a pre-colonial Somali ethnic heritage area. We wanted to visit a safe, small place that might afford us opportunities to learn about the Horn and about refugee camps similar to those we had long heard about in Minnesota. It is logistically and culturally easy for foreigners to travel to Djibouti and the scale and pace of the capital city is remarkably manageable. As safety in the region increases, we hope to broaden our collaborations; but in the interim, we envisioned Djibouti as a place for us and other educators to begin.

As we learned about Djibouti, Jill and I were stunned that we did not recall ever hearing about or meeting anyone from Ali Addeh refugee camp. We have Djiboutians in Minnesota, but they are few and likely lumped together with people from Kenya, Ethiopia, or Somalia. In other words, people who identify as ethnically Somali are considered Somali, even if they are from Djibouti or elsewhere. Data from the Census Bureau’s Population Estimates Program calculates that in 2017 there were no Djiboutians or Eritreans in Minnesota, a fact easy to refute given our acquaintances from these countries. Estimates for people with Somali (52,333), Ethiopian (21,996), and Kenyan (4,277) ancestry are also likely low, but do reflect our sense of the proportions of people claiming these nationalities, which often intersect more with ethnicity in the case of people who are have a Somali identity. This is because people of Somali ethnicity come from all of the countries of the Horn and now from many large Diaspora communities worldwide (e.g., UK, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Denmark).

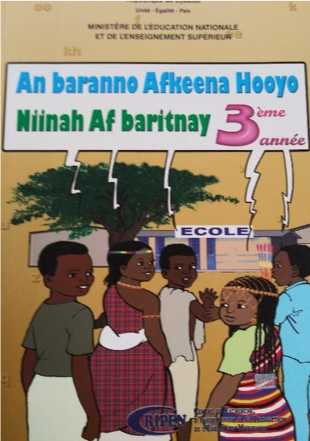

Djibouti is a small country with a population of only about one million people and a total area of approximately 9,000 square miles. It is the only French speaking country in the region and is ethnically Somali (60%) and Afar (35%) with most people speaking one or both of those two languages in addition to French and Arabic. The language of instruction in Djibouti in French and other languages such as English and Arabic are taught as foreign languages. The Ministère de l’Éducation enthusiastically produces multilingual materials for K-12 Djiboutian students. This is a photo of third grade textbook in Somali and Afar designed specifically for Djiboutian students who are in French medium schools. With materials such as this, elementary age students’ cultural and linguistic identities are affirmed at school, as they learn through French.

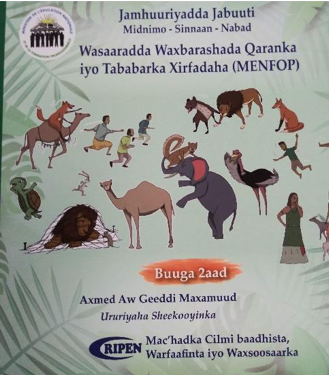

We also saw materials designed to make reading enjoyable in the mother tongue. This is an example of a book of Somali folktales. The pictures on the cover of the book make it easy for children to link to stories told in their homes. These examples, of which there are many more, beg the question: How is it possible for a small country such as Djibouti to produce so many multilingual materials, when our wealthy country and state cannot?

The Ali Addeh Refugee Camp

Education in Djibouti also includes a well-developed and similarly controlled education system at the refugee camps within its borders. The Ministère de l’Éducation produces materials for the schools in the camps and offers administrative oversight as well as support.

To give readers some background about the camps, according to the UNHCR, there are approximately 27,601 refugees in Djibouti and the Ali Addeh refugee camp has approximately 15,676 refugees mainly from Somalia, Ethiopia, Yemen, and Eritrea. (This is small compared to, for example, the 212,936 registered refugees and asylum seekers in Dadaab Refugee Complex in 2019.) There are two other smaller camps in Djibouti—Holl Holl and Obock—and many refugees live outside the camps, including in Djibouti City. As a point of comparison, Minneapolis Public Schools has approximately 36,000 students and Saint Paul Public Schools has approximately 38,000 students.

When we went to Ali Addeh, we had the opportunity to visit various K-12 schools that most, if not all, children in the camp attend.

The education practices in the Djiboutian refugee camps had many admirable and progressive policies, for example:

- It is possible to earn a Djiboutian high school diploma by attending these schools, in the same way the children in the French medium school obtain diplomas.

- The teachers are from the camps and from Somalia, Ethiopia, and Eritrea, which offers adults a vocation, often the same as they had prior to being displaced, and an income.

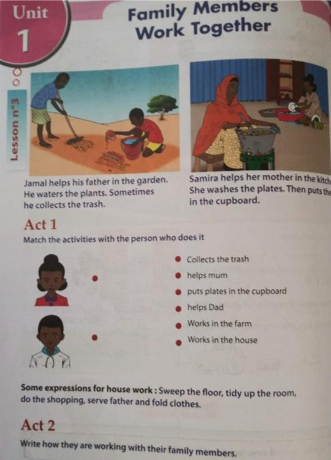

While French is used for instruction in the rest of the country, the director of Ali Addeh camp explained that English was selected as the language of instruction in all subject areas, to better prepare students for life after resettlement. The English materials specifically designed for the children in the Ali Addeh camp were of the same quality as those produced for the Djiboutian children. This is an example of a page from a civics book for elementary age children:

The materials consider the realities of life in the refugee camp in ways that seem, from the perspective of outsiders, culturally appropriate. Children graduate from the schools in the camp as they await resettlement. We heard from educators that the majority are not resettled and even the best students are not able to find employment. This desperation is part of a system far beyond the control of teachers, the camp administration, the Djiboutian government—it’s a global problem for which we’re all responsible.

Conclusion

We can learn from Djibouti. There are clear lessons learned for our context, even without more and much needed further study:

- Intake systems in schools need to account for a wide range of backgrounds of children from refugee camps who are new arrivals to the country. They do not all have limited formal schooling. Consider a literacy screening device like the one Kendall King and I developed, asking for diplomas and high school transcripts.

- Somali refugees may have been schooled in English in Kenya and Djibouti—but that looks vastly different across these two contexts.

- If newcomers to Minnesota come from Ali Addeh, they have had many years trying to imagine themselves in an English-speaking life. What does it mean for them if English is treated as a foreign language in the schools they attend and they need to learn Swedish, Finnish, German, or perhaps French or some other language? Their imagined community suddenly will have shifted. On the other hand, multilinguals, such as those coming from Ali Addeh, may not see learning a new language as a daunting task, given that they are likely to have age/grade appropriate literacy in English already.

One of the most important questions I was left with is why don’t we offer multilingual materials for all of our small populations? We have legislation that supports multilingualism broadly in Minnesota and immersion programs are able to gather and write curricula across all grades and subjects. But materials in the languages of our immigrant groups are not available; even our most commonly represented linguistic minority groups do not benefit from any coordinated, systematic, or professional effort to provide them with materials in their languages and that reflect their lives. It must be that Djibouti, despite their small size and limited resources, believes in the importance of students’ languages and cultures being included in their schooling experiences. In other words, it seems that the barrier in the U.S. is largely ideological, not financial. In so many multilingual contexts, ideologies such as the following still prevail:

- Cultural plurality still coincides with adding the dominant language and culture.

- There needs to be a common language for a unified society.

- Families, places of worship, and communities are primarily in charge of maintaining minority languages, not schools. School is a place to learn the majority language and culture.

The children in the refugee camps in Djibouti are studying hard, and learning English to a very high level of proficiency. There is hope that English is a pathway to a better future for them. We don’t know if they will ever be resettled, or that they’ll be resettled to a place where English will help them make healthy, successful, and happy lives. Optimistically and responsibly, the Djiboutian Ministère de l’Éducation continues to educate the refugee children in ways that reflect how they would educate their own children, in ways that they hope will resonate with the children’s lives, and that will serve them in their very uncertain futures. What if we all took up this very serious goal of teaching multilingual children multilingually?

Coda

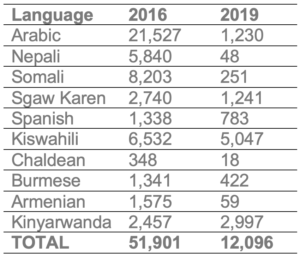

The U.S. is on a path to no longer being a receiving country for refugees. The number of refugees resettled in the U.S. has been very low, particularly given our resources and size. Under the current federal administration, the U.S. plans to admit a maximum of 18,000 refugees in 2020, down from 30,000 in 2019, the lowest number since 1980 when Congress created the U.S. refugee resettlement program. Compare this number to 207,116 in 1980 or 60,191 in 2008, nationwide. Data in the following table from the U.S. Department of State on the top 10 languages spoken by refugees in the U.S. reflect the loss of cultural and linguistic diversity in the U.S.

The following list of top 10 languages spoken by K-12 students in Minnesota (besides English) in the 2018-2019 academic year reflects our proud and strong immigrant and refugee communities:

Spanish 49,657

Hmong 20,409

Somali 27,505

Karen 4,240

Vietnamese 4,024

Arabic 3,179

Mandarin 2,526

Russian 2,494

Oromo 2,472

Amharic 1,849

Between October 2018 and September 2019, Minnesota welcomed only 848 refugees according to the Department of State Refugee Processing Center.

According to the UNHCR, there are now 70.8 million forcibly displaced people worldwide. There is more need than ever to receive refugees. But as the number of refugees resettled in the U.S. decreases, so do services for refugee-background youth and families. It will take many years to re-establish the newcomer programs and services that are disappearing, thus making it extremely challenging to become a place once again that has the capacity to resettle refugees as well as we have, for so many decades.

I believe that our current federal refugee resettlement policies are taking us in the wrong direction and will have a profound and negative impact on our state—educationally, culturally, and linguistically. Minnesota has the tradition and the capacity to help address the worldwide refugee crisis. We must resist compassion-less federal policies and isolationist ideologies that ignore the level of displacement that is occurring in so many places in the world and stand in solidarity with our refugee-background communities.

Notes

- The Dadaab Refugee camp in Kenya is the topic of numerous books (e.g., What is the What by Dave Eggers and Achak Deng, and City of Thorns by Ben Rawlence), scholarly work (e.g., Analysis of the financial activities of refugees in Dadaab, Kenya), and films (e.g., Warehoused: The Forgotten Refugees of Dadaab). I’ve also seen an emerging genre of invaluable first-person accounts from Somali young adults who survived their migration experience out of Somalia, often to another country in the Horn or elsewhere in Africa, and have much to say about life in the Diaspora (e.g., Angry Queer Somali Boy: A Complicated Memoire by Mohamed Abdulkarim Ali; Call Me American: The Extraordinary True Story of a Young Somali Immigrant by Abdi Nor Iftin).

References

Bigelow, M. (2010). Mogadishu on the Mississippi: Language, racialized identity, and education in a new land. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Bigelow, M. (in press). The case of a Somali teenage girl with limited formal schooling: Seeing assets and poking holes in deficit discourse. In A. Cooper, & A. Ibrahim (Eds.), Black voices matter: Black immigrants in the United States and the politics of race, language, and multiculturalism. New York: Peter Lang, International Academic Publishers.

Bigelow, M., & King, K. (2014). Somali immigrant youths and the power of print literacy. Writing Systems Research, 6(2), 1-16.

Bigelow, M., & King, K. (2016). Peer interaction while learning to read in a new language. In M. Sato, & S. G. Ballinger (Eds.), Peer interaction and second language learning (pp. 349-375). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Bigelow, M., Vanek, J., King, K., & Abdi, N. (2017). Literacy as social (media) practice: Refugee youth and home language literacy at school. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 60, 183-197.

King, K., & Bigelow, M. (2018). The language policy of placement tests for newcomer English learners. Educational Policy, 32(7), 936-968.

King, K., Bigelow, M., & Hirsi, A. (2017). New to school and new to print: Everyday peer interaction among adolescent high school newcomers. International Multilingual Research Journal, 11(3), 137-151.

King, K., & Bigelow, M. (in press). The hyper-local development of translanguaging pedagogies. In E. Moore, J. Bradley, & J. Simspon (Eds.), Translanguaging as transformation: The collaborative construction of new linguistic realities. Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.